Photos courtesy of Richard Kerns from Odyssey Earth

At the beginning of April, scientists, business professionals, and policy-makers from across the globe gathered in Havana at the third International Workshop of Fish, Pollution, and the Environment to discuss sustainable development and the use of marine resources in Cuba. Cuban leaders invited Bonefish & Tarpon Trust to the conference; Dr. Ross Boucek, BTT’s Florida Keys Initiative Manager, and Dr. Jennifer Rehage, a BTT collaborator from Florida International University, both attended. Dr. Boucek presented an overview on BTT’s approach to protecting flats fisheries, and how it could be applied for habitat conservation in Cuba.

“Our process to protecting flats fisheries is straightforward,” said Dr. Boucek. “First, we calculate how much money the flats fishery generates for local and regional economies. Second, through science, we identify juvenile habitats, adult habitats, and spawning sites of bonefish, permit, and tarpon. Lastly, we provide this information to government officials and community leaders, with the message that if these juvenile habitats, adult habitats, and spawning sites are protected, and harvest is minimized, then these fisheries that generate large sums of revenue will continue to be profitable of years to come.” Dr. Boucek also briefed the audience on BTT’s Bahamas Initiative, and how BTT used economics and its science-based approach to work with the Bahamian government to establish six national parks to protect bonefish juvenile and adults habitats and spawning sites.

Dr. Rehage, whose research is focused on understanding why our bonefish fishery in the Keys has collapsed, gave a precautionary presentation on the history of Florida and the missteps we have made along the way that has led to the decline in our fisheries. “We have multiple interacting factors related to Florida’s population growth that have contributed to the declines of our fisheries,” said Dr. Rehage, “particularly hydrological modifications, loss of habitats and declines in habitat quality, and possibly contaminants.” Rehage added “it is important and valuable for us in the Keys to understand what fisheries look like in such pristine conditions like in Cuba, because this helps guide restoration efforts here. On the  flipside, our already stressed south Florida environment provides a cautionary note of undesired trajectories for tourism development in places like Cuba.”

flipside, our already stressed south Florida environment provides a cautionary note of undesired trajectories for tourism development in places like Cuba.”

In terms of conservation, Cuba has an opportunity to be proactive and protect important habitats. Already, habitat protection schemes are sustaining world-class fisheries in Cuba. On the Southwest side of the island, Las Salinas sits just west of the Bay of Pigs, an estuary that from a satellite image, does not look very different from Florida Bay.

Las Salinas

Unlike Florida Bay, there is no development, no water quality issues, commercial netting is banned, and only about a dozen fishing guides are permitted to fish the area. Further, those few fishing guides are only allowed to fish certain spots on a given day, ensuring that bonefish permit and tarpon don’t get too much pressure. The result: there are healthy habitats, and world-class fishing for bonefish, permit and tarpon.

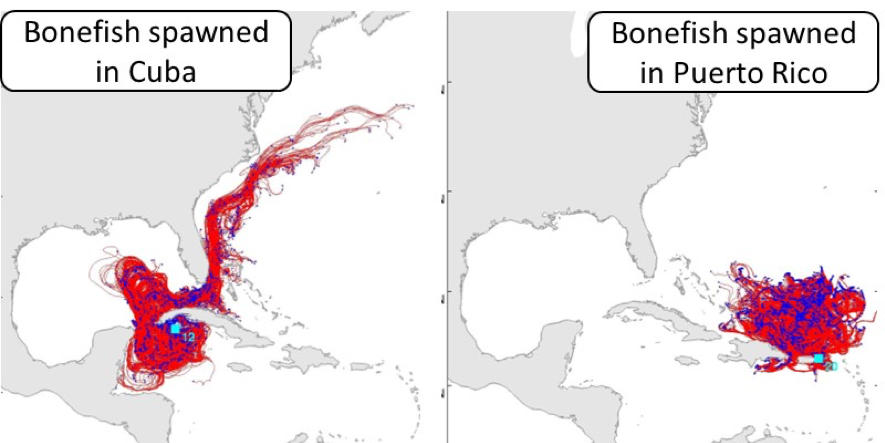

The Florida Keys flats fishery may be linked to Cuba’s future as well. In the Keys, an important conservation question is where does Florida Keys bonefish larvae come from? Bonefish have a unique trait; their larvae float in open ocean currents for nearly two months before settling in nursery habitats. This means that the parents of our Keys bonefish could possibly occur anywhere through the Caribbean. To narrow down where our bonefish parents are from, BTT worked with Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service to run ocean current simulation models to predict where a bonefish larvae spawned in various places throughout the Caribbean would land. These models suggest that bonefish spawning on the Southwest side of Cuba could supply the Keys with larvae, and therefore may be the parents of some portion of the Keys population.

Ocean current models that predict where bonefish larvae drift to after 30 days (blue) and after 60 days (red). This modeling effort shows that bonefish spawned in Cuba could reach Florida, while bonefish spawned in Puerto Rico likely will not.

This connectivity between Cuba and the Keys means that the fate of our fisheries are linked to some degree. As the border between Cuba and the U.S. becomes more open in the future, Bonefish & Tarpon Trust will be available to help develop conservation programs to protect flats fisheries there, not only for the sake of protecting Cuba’s world-class fisheries, but also for protecting ours in the Keys.