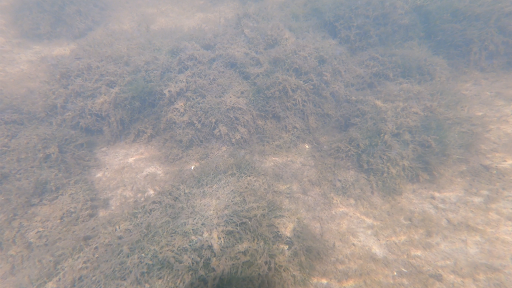

What used to be an expansive seagrass flat that is now a mix of open sand and thick algae.

By Aaron Adams, Ph.D., BTT Director of Science and Conservation

The cancer of too many nutrients is spreading throughout Charlotte Harbor. This does not bode well for the long-term future of its legendary fisheries.

I lived on Pine Island for 12 years, starting in 2001. The flats from southern Pine Island Sound to Punta Gorda and Cape Haze were my home waters. Like others who know their home waters well, I could navigate the backcountry by recognizing individual mangroves, run the troughs in the flats by memory. Even a full moon or twilight dawn sky gave enough light to make the runs. After moving to Florida’s east coast, my backyard became the Indian River Lagoon, but I couldn’t escape the draw of Charlotte Harbor’s flats, and frequently hauled my skiff across the state to fish.

I’ve been away from Charlotte Harbor for the past four years. First the extended red tide, and then numerous other issues kept me away. Last week, I returned – in part to join colleagues to film for a video on BTT’s juvenile tarpon and snook habitat research, and in part to fish my old haunts.

Upon reaching my favorite backcountry area, I was devastated. It was nothing like it once was. And this isn’t a case of looking back through rose-colored glasses.

In the past, the habitat transitioned as I poled from the grass flats into the backcountry. Turtle Grass on the flats gave way to Shoal Grass among the mangrove islands. Then there was a band of mostly sand bottom – the transition area that during winter was salty and during summer was freshwater due to the many creeks that disappeared into the mangrove forest and drained the summer rains. Then farther up the creeks I’d find Widgeon Grass – a species that was able to handle the full freshwater of summer. The upper reaches are juvenile tarpon and snook nursery habitats.

Charlotte Harbor is extremely sick. Vast mats of green algae cover the bottom over expansive areas of flats and backcountry. Areas that were once seagrass are either covered by algae or are completely barren. Flats where I once sight-fished for redfish tailing in thick beds of turtle grass are now bare sand bottom.

This massive algal bloom is impacting all habitats – from juvenile nurseries to habitats used by adults.

The fact that this algae was becoming an issue wasn’t news to me. Numerous friends from Charlotte Harbor – guides and anglers – shared photos and videos with me over the past few years, and BTT has made several social media posts using these images to sound a warning.

But that warning is now an air-raid siren.

Just as expansive and seemingly never-ending, harmful algal blooms caused by plankton have decimated the Indian River Lagoon, and I fear that Charlotte Harbor is suffering a similar fate, this time to an expanding benthic (benthic = on the bottom) algae bloom. Sadly, the results will be the same – loss of seagrass and the communities that depend on seagrass beds. In the Indian River Lagoon, I can pole my skiff across sand flats for eight miles north from the Sebastian Inlet and not see a blade of seagrass. I recently covered far more water than that in Charlotte Harbor and saw very little seagrass. Instead, I encountered thick mats of algae from the flats to the farthest reaches of the backcountry.

As in the Indian River Lagoon, Charlotte Harbor’s decline is from too many nutrients: leaky septic systems, fertilizer, outdated sewage infrastructure, stormwater runoff, industry effluent… the list goes on.

Without healthy habitats – and water is the most important habitat of all – our fisheries will continue to decline. The maximum amount of fisheries management won’t be enough to make up for continuing habitat declines.

That wasn’t the trip I was hoping for. I’m devastated. You should be too.