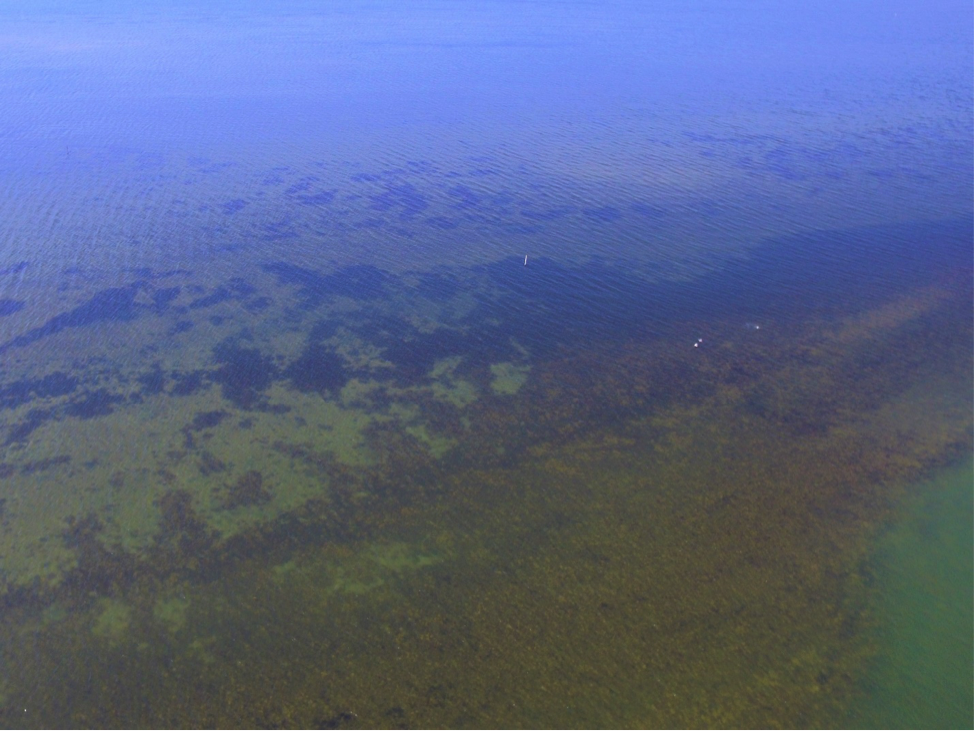

An aerial view of a large ridge of drift algae in the IRL, April 2021. PC: Mitch Roffer

By Aaron Adams, Ph.D., BTT Director of Science and Conservation

Last month I shared my dismay at seeing the poor state of Charlotte Harbor when I towed my skiff over there for work and fishing. The post generated a lot of comments and shares, which is great. The more we raise public awareness about these important issues (and the more people who reach out to their political representatives demanding change) the better chance we have to change the management policies that have caused these habitat and water declines.

Being as addicted to fishing as I am, I couldn’t help but splash my skiff in the Indian River Lagoon last week. Although I was expecting to fish over open sand flats and see little or no seagrass (the Indian River Lagoon has lost more than 70% of its seagrass due to poor water quality and algae blooms), I wasn’t expecting to see as much algae as I saw.

You’ll remember from my post about Charlotte Harbor on March 1, that Charlotte Harbor is suffering from massive mats of benthic (benthic = on the bottom) algae. That algae smothered seagrasses, resulting in vast flats of open sand and thick piles of algae.

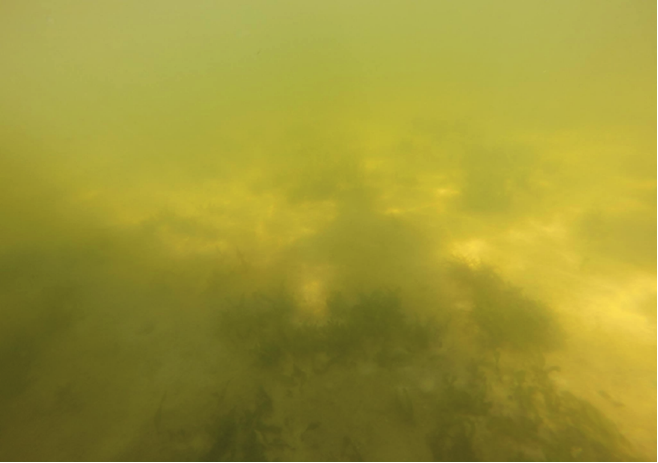

In contrast, the Indian River Lagoon has mostly suffered from plankton algae blooms – microscopic, single-celled algae that fill the water column. These plankton algae blooms shade the sun, and without enough sunlight the seagrasses die. Then when the algae die the decay process sucks up much of the oxygen in the water, which causes fish kills.

As if these plankton algae blooms weren’t bad enough, now the benthic algae in the Indian River Lagoon is beyond being out of control. The benthic algae in the IRL is different than what I saw in Charlotte Harbor. The Charlotte Harbor algae was one or more species of green algae that I hadn’t seen before. The Indian River Lagoon algae are species of brown and red algae that are called ‘drift algae’. They are called drift algae because they drift along the bottom, moved by wind and currents, like tumbleweeds.

These species of drift algae have always been relatively common in winter months. But now these drift algae are so abundant that they cover acres upon acres of bottom, in some places piled more than three feet deep. These vast mats of algae prevent any new seagrass shoots from surviving, reinforcing a vicious cycle that keeps the bottom barren. And after a few windy days, algae piles along shorelines where it rots.

The drift algae is out of control because, despite ongoing work to address the problem, the Indian River Lagoon still has far too many nutrients, and fixing the lagoon is not a high enough priority for some. Wastewater and stormwater problems continue to plague the lagoon, delivering too many nutrients, further fueling algae blooms.

The IRL is now in a vicious cycle. During summer rainy season, runoff carrying too many nutrients flows into the IRL. The plankton algae jump on this source of nutrients and warm summer temperatures to bloom. This shades seagrass that is trying to recover and causes fish kills. Then as the water cools in winter and dry season means less rain, the IRL waters tend to get very clear, which is great for benthic plants to grow. In a healthy system seagrass is able to take advantage of the clear water. But now the drift algae has taken over, knocking back any seagrass recovery once again. Throughout the year wastewater – from leaky septic systems and outdated sewage treatment – introduces nutrients into the lagoon.

The IRL didn’t collapse to its present state overnight, and it’s going to take time to fix it. But the fix will come only if we keep pressure on policymakers to change the way business is done and to prioritize responsible management. That’s going to take continued input from all of us. Contact your local, state, and federal representatives and let them know that restoring and protecting our estuaries and fisheries needs to be a top priority.

If we could put men on the moon just ten years after President Kennedy made his declaration, we can fix our estuaries. We just need to make it a priority.