In January 2016, BTT began its Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Mapping Project that uses anglers to identify nursery habitats harboring tarpon 12 inches or less and assesses them as natural or altered/degraded. Over 65% of the angler-reported habitats were classified as altered or developed. One solution to rectify the immense amount of coastal habitat loss is to fix the habitats that are only marginally degraded. The designs for these projects are intended to mimic a more natural system and are referred to as habitat restoration.

BTT’s first completed habitat restoration project, Coral Creek Preserve, was originally developed as a residential community with saltwater access that was left abandoned. The Coral Creek project has six adjacent canals connected by a main canal that has an inlet to the west branch of Coral Creek. The original habitat restoration plan was to fill in the canals and return them to their natural pine flatwood topography. But after the realization that juvenile tarpon inhabited one of the canals, the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) decided to change their plans.

From previous studies, we know many of the habitat characteristics commonly found in tarpon nursery habitats, but we don’t know which ones are most important. With the help of Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program (CHNEP) scientists and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), we settled on three different experimental designs that would each be duplicated and randomly assigned to the six canals.

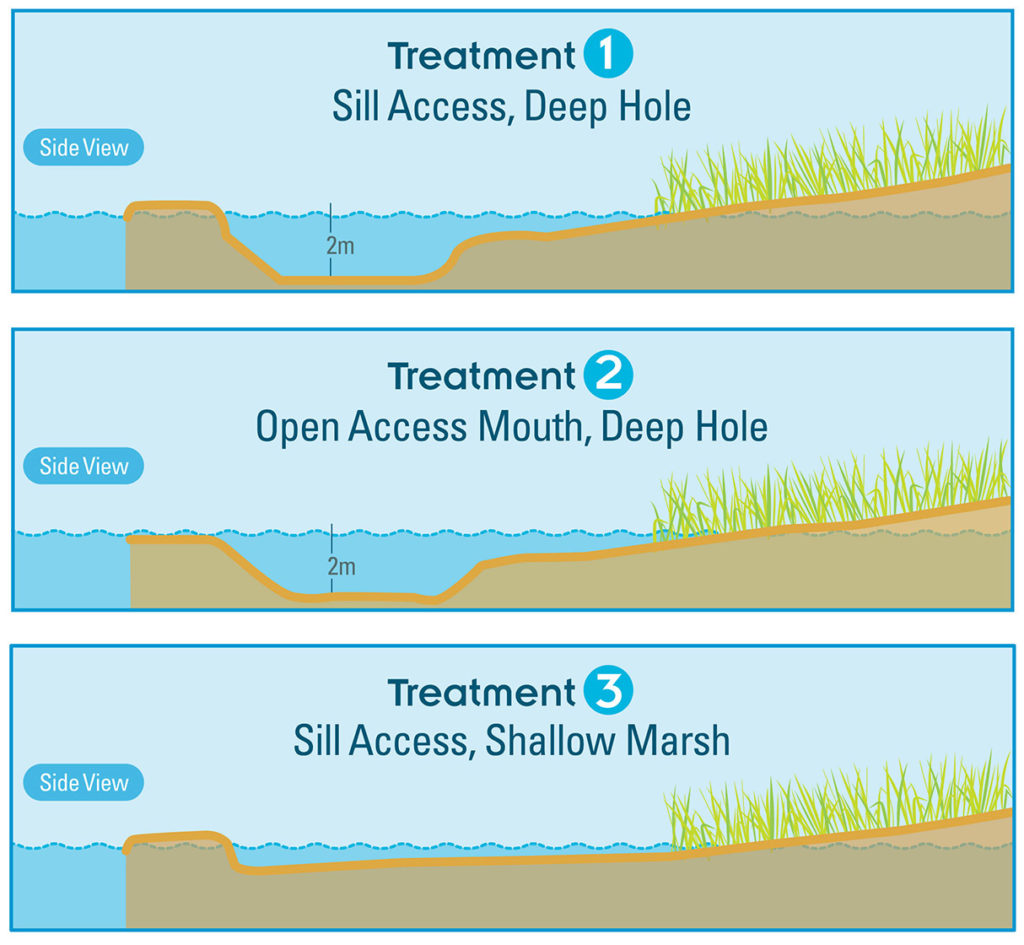

The first design features a sill mouth at the connection to the main canal which acts as a restrictive barrier during low tides. We often see restricted access in nursery habitats which benefits juvenile fish by excluding large predators from entering. During our previous juvenile tarpon research at nearby Wildflower Preserve, we saw that the majority of juveniles emigrated from (or left) the nursery habitat during the summer months. The summer months in southwest Florida are when we typically have our highest water levels, therefore the sills would not impede the juvenile tarpon from leaving. We also included a deep hole followed by a shallow creek. Juvenile tarpon spend multiple seasons and potentially multiple years in the nursery habitat. The deep hole serves as a temperature refuge by providing warm water during cold snaps and cooler water in the prolonged summers. Juvenile tarpon can also be seen rolling at the surface to “gulp” air because of the low dissolved oxygen in these backwater habitats. Although the low oxygen content helps to keep large fish out of these habitats, the rolling behavior likely rings the dinner bell for wading birds that can frequent these habitats. There is some research to suggest that tarpon can hide in the deep holes to evade bird predators.

The second design also includes the deep hole, but instead of a sill mouth we included an open flowing connection that is continually accessible by fish. This gives us a chance to test the theory that the sill mouth prevents predator access and is in fact an essential nursery habitat characteristic. Although this will provide access to predators, it will also give tarpon the chance to move in and out of this particular habitat treatment throughout the year. Studies on juvenile snook show that, like humans, some have a preference for travel while others are “homebodies.” If this is the case for tarpon, that is vital information that we need for future design plans.

The third and final design includes the tidally exclusionary sill mouth of design #1, but forgoes the deep hole and follows the topography of a meandering shallow creek. This treatment allows us to compare the importance of the deep hole as a necessary nursery habitat element. The dark estuarine water with mere inches of visibility may provide enough cover from predatory birds looking for an easy meal and the deep hole may not be necessary.

One question we’re occasionally asked is “if there’s tarpon there, doesn’t it mean it’s a good habitat?” The answer – not necessarily. The presence of juvenile tarpon in a habitat seems to be a false indicator of habitat quality, which came to light at Wildflower Preserve, an altered habitat in southwest Florida and another BTT habitat restoration project. Growth rates of fish are a reliable measure of habitat quality and although we found large numbers of juvenile tarpon at Wildflower Preserve, growth rates were extremely slow – 1” per year at Wildflower versus 10” per year in other studies.

Therefore, we can’t solely use presence or absence of a species as the only determination for habitat health. Most importantly, this reminds us that we can no longer sit idly by as vital nursery habitats are impacted by coastal development, changing water flows and nutrient runoff. Habitat restoration is the solution for cleaning up the mess we’ve created.

Over the next 12-18 months, we’ll be sampling monthly at Coral Creek, which includes PIT tagging all captured juvenile tarpon. From PIT tagging, we can measure growth rates, estimate survival rates and abundance, and track tarpon movement throughout the various treatments and as they make their final emigration out of the nursery habitat. The completion of the nursery habitat restoration project at Coral Creek Preserve will not only increase the amount of quality nursery habitat in the region, it will also give us a better idea of what juvenile tarpon need. BTT’s mapping project has compiled a list of priority sites that make excellent candidates for habitat restoration. Once we know what tarpon want, we’ll be able to replicate those design elements in future habitat restoration projects and slowly change the ratios of “degraded” nursery habitats to restored.